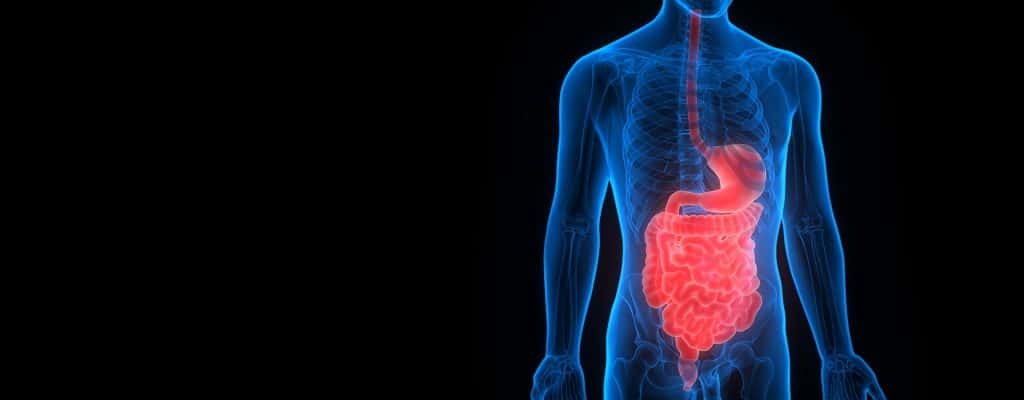

Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) is an umbrella term used to describe two main diseases: Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis. Both of these diseases cause inflammation to the bowel. IBD should not be confused with Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS), a disease that may present with some similar bowel symptoms (diarrhoea, abdominal pain, constipation, bloating) but tests reveal no indication of inflammation. IBD and IBS are quite different and require different modes of treatment. The inflammation present in IBD is thought to be due to a dysfunction in the immune system rather than an infection (Digestive Health Association, 2013).

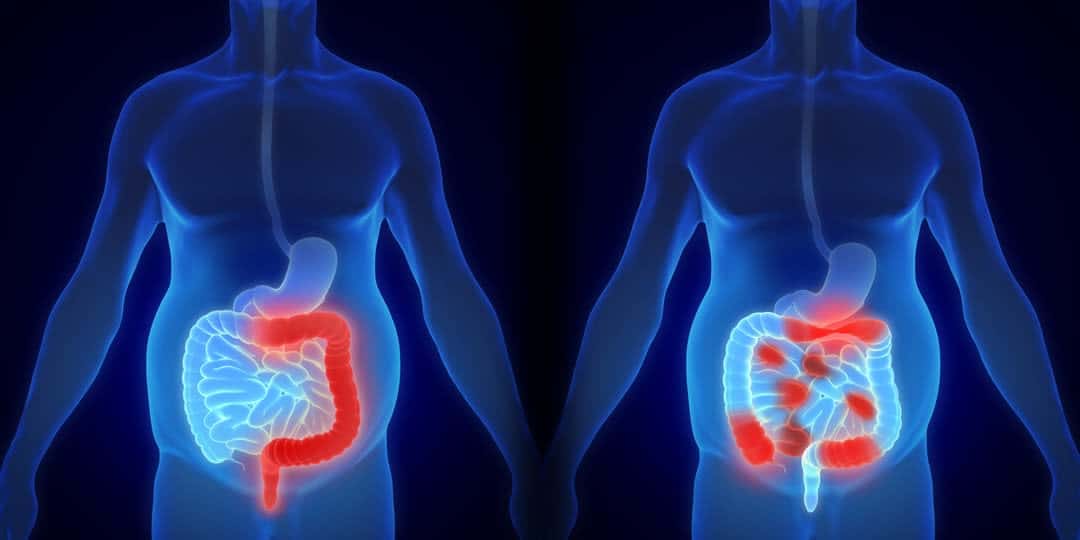

Crohn’s Disease causes inflammation of the full thickness of the bowel and can affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract from the mouth to the anus. Ulcerative Colitis causes inflammation only of the inner lining of the gastrointestinal tract and affects only the colon and/or rectum.

What causes IBD?

Despite extensive research, the causes of IDB are still unknown. There is evidence to suggest genetic, environmental, immunological, and infectious factors may all be involved to a degree (Digestive Health Association, 2013). These factors may cause a fault in the immune system that in turn causes inflammation in the bowel (Australian Government Department of Health, 2018). These diseases can develop at any age, but tend to appear in people aged 15 to 30.

In line with the role of a genetic factor, relatives of people with IBD disease have a slightly greater risk of developing IBD themselves. Additionally, certain ethnic groups are more likely to develop these conditions, for example Caucasians. Researchers have identified several genes common in peoples with IBD but have not been able to show that any of these genes play a causative role in the development of the disease.

Diet and stress are not thought to be the cause of IBD alone, but attention to both of these factors can significantly improve quality of life with IBD. No diseases under the umbrella of IBD are contagious. Prevalence is greater in the Western world, such as Australia, Western Europe and America, although incidences are rising in developing countries such as Asia and Africa (Digestive Health Association, 2013). It could be that the Western lifestyle plays a role in the development of IBD in susceptible people.

Exposure to certain environmental triggers such as bacteria or viruses prompt the immune system to switch on its normal defence mechanism – inflammation. In most people, this immune response will gradually wind down as the foreign substance is destroyed. In some people with a susceptibility to IBD, the immune system fails to switch off and continues with inflammation. Prolonged inflammation eventually causes damage to the walls of the gastrointestinal tract that manifests as the symptoms of IBD (Crohn’s and Colitis Australia, 2020).

Symptoms

IBD manifests differently in each person and symptoms are dependent on where in the gastrointestinal tract the inflammation is present, and how severe. Symptoms can range from mild to severe but tend to include the following:

- Abdominal pain and cramps

- Diarrhoea (often with blood and mucous with Ulcerative Colitis)

- Anaemia due to blood loss

- Severe urgency to have a bowel movement

- Tiredness/fatigue

- Weight loss (especially with Crohn’s disease) and loss of appetite

- Fever

- Mouth ulcers

- Nausea and vomiting

- Pain or swelling around the anus

- Swollen joints

- Inflamed eyes

- Skin lumps or rashes

- Jaundice

IBD is a chronic (ongoing) disease and symptoms may come and go depending on the degree of inflammation. When inflammation is severe, this is considered the active stage. When inflammation is less severe or absent, symptoms may disappear, and the disease is considered to be in remission. Most people will experience periods of remission interspersed with periods of severe inflammation. Life expectancy is normal with current medical treatment.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of mild IBD is often delayed as the symptoms frequently occur in other diseases. Generally, unless symptoms have been ongoing for greater than 8 weeks it is necessary to exclude bowel infections or gastroenteritis first. IBS is often the first diagnosis in mild cases of IBD as the condition is far more common. However, the discovery of any abnormal test results should guide the way to an IBD diagnosis (Digestive Health Association, 2013). Your GP may request blood tests to look for indications of IBD such as anaemia, elevated white cell or platelet count, and elevated CRP or ESR (inflammation markers in the body). Blood tests can also reveal other indications of the disease such as iron deficiency, or other vitamin or mineral deficiencies. A faecal specimen may be required to exclude infection.

Most cases will require examination of the bowel either via colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy or gastroscopy. The bowel can also be examined through x-rays which may include CT, MRI or barium small bowel series (where dye is swallowed, and x-rays are taken). Unfortunately, there is no one test that can reliably diagnose all cases IBD, the diagnosis is reached through careful examination of medical history and detection of inflammation in the gastrointestinal tract through a variety of tests.

Treatment

Treatment varies depending on the type of IBD you have (Crohn’s disease or Ulcerative Colitis), where the inflammation is located in the gastrointestinal tract, and the severity of the disease.

Crohn’s Disease

This disease involves periods of active disease, and periods of remission. The aim of treatment is to treat the inflammation during periods of activity and give the bowel a chance to heal. Medications can be used to help prolong remission, improve general wellbeing, and help prevent further complications from developing. Commonly used medications to treat inflammation include:

- Steroids

- Aminosalicylates to control the frequency of relapses

- Medications that suppress the immune system

- Antibiotics

You may also be advised to take supplements such as iron, vitamin D and calcium. Pain relief and medications to control diarrhoea can also be used.

In some cases, surgery can be undertaken to remove or widen parts of the bowel that are badly affected by the disease. The healthy ends of the bowel can be re-joined. In particularly severe cases, a stoma can be considered. A stoma is an artificial opening in the stomach that diverts urine or faeces into a bag outside of the body. It is normal to feel uneasy about the idea of living with a stoma, but it often greatly improves the quality of a person’s life (Australian Government Department of Health, 2018).

Ulcerative Colitis

As with Crohn’s Disease, Ulcerative Colitis also involves periods of severe inflammation and periods of remission. The same medications can be used to treat the periods of inflammation, and the same supplements may be recommended.

If the colitis is severe and does not respond well to medications, your doctor may recommend surgery to remove the colon (Australian Government Department of Health, 2018). A pouch is then created inside the body using the small intestine, and this pouch is connected to the anus. Another option is the use of a permanent or temporary stoma.

How Important is Diet?

Most people with IBD do not need to eat special food and can eat a healthy, balanced diet. It is particularly important to eat enough to prevent weight loss, and sometimes nutritional supplements are advised to prevent deficiencies and maintain their weight. There is no evidence to suggest that IBD is caused by food allergies or intolerances. You may find though that certain foods can worsen your symptoms, such as spicy foods, fatty foods, and high fibre foods (e.g. some fruits, vegetables, nuts, and wholegrains). If this is the case, it is sensible to reduce your intake of such foods. Some people with Crohn’s disease are unable to absorb certain nutrients and may need to take supplements. This is uncommon in Ulcerative Colitis; however, this disease can cause anaemia due to blood loss. For assistance in identifying food groups that may worsen your symptoms, and creating a healthy and balanced diet, you can book in with one of our dietitians.

In addition to diet, it is important to manage your stress when living with IBD. Regular exercise and learning some relaxation techniques can help to manage stress. For more advice on stress management, you can book in with one of our doctors.

Living with IBD

Most people living with IBD lead happy and productive lives, even though they need to take medications. When their disease is in remission, they are usually symptom free and feel well. Even though there is no cure of IBD, with proper management the disease can be maintained, and you can lead a full life.

At Medsana, our team of medical practitioners can work together to create a management plan to optimise your quality of life living with IBD. For further support, you may also consider joining Crohn’s and Colitis Australia.

The information in this article has been adapted from:

Australian Government Department of Health. (2018). Crohn’s Disease. Retrieved from Health Direct: https://www.healthdirect.gov.au/crohns-disease

Australian Government Department of Health. (2018). Ulcerative Colitis. Retrieved from Health Direct: https://www.healthdirect.gov.au/ulcerative-colitis

Crohn’s and Colitis Australia. (2020). About Crohn’s and Colitis. Retrieved from Crohn’s and Colitis Australia: https://www.crohnsandcolitis.com.au/about-crohns-colitis/

Digestive Health Association. (2013). Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Retrieved from Gastroenterological Society of Australia: https://www.gesa.org.au/resources/patients/inflammatory-bowel-disease/

This article was written by April Stevens BSc. MD student.

22nd October 2020.